Queer Places:

Welcombe House, Warwick Rd, Stratford-upon-Avon CV37 0NR, UK

Wallington Hall,

B6342, Cambo, Morpeth NE61 4AR

Harrow School, 5 High St, Harrow, Harrow on the Hill HA1 3HP

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Holy Trinity Churchyard

Chapel Stile, South Lakeland District, Cumbria, England

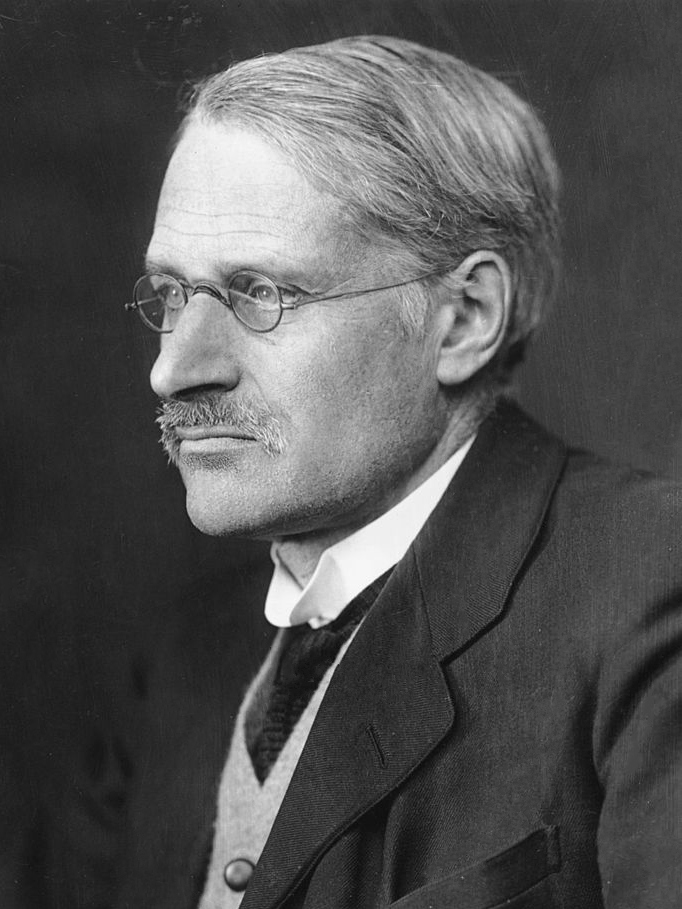

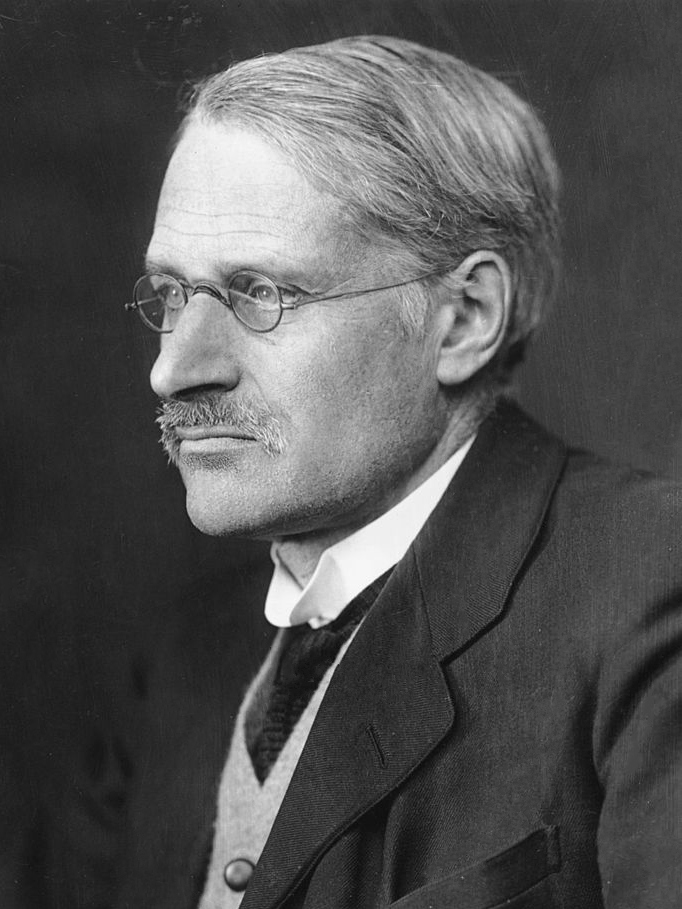

George Macaulay Trevelyan OM CBE FRS FBA (16 February 1876[2] – 21 July 1962),[3] was a British historian and academic. He was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1898 to 1903.

He was part of the Cambridge

Apostles. He then spent more than twenty years as a full-time author. He returned to the University of Cambridge and was Regius Professor of History from 1927 to 1943. He served as Master of Trinity College from 1940 to 1951. In retirement, he was Chancellor of Durham University.

Trevelyan was the third son of Sir George Otto Trevelyan, 2nd Baronet, and great-nephew of Thomas Babington Macaulay, whose staunch liberal Whig principles he espoused in accessible works of literate narrative avoiding a consciously dispassionate analysis, that became old-fashioned during his long and productive career.[4] The noted historian E. H. Carr considered Trevelyan to be one of the last historians of the Whig tradition.[5]

Many of his writings promoted the Whig Party, an important aspect of British politics from the 17th century to the mid-19th century, and its successor, the Liberal Party. Whigs and Liberals believed the common people had a more positive effect on history than did royalty and that democratic government would bring about steady social progress.[4]

Trevelyan's history is engaged and partisan. Of his Garibaldi trilogy, "reeking with bias", he remarked in his essay "Bias in History", "Without bias, I should never have written them at all. For I was moved to write them by a poetical sympathy with the passions of the Italian patriots of the period, which I retrospectively shared."[4]

George Macaulay Trevelyan OM CBE FRS FBA (16 February 1876[2] – 21 July 1962),[3] was a British historian and academic. He was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1898 to 1903.

He was part of the Cambridge

Apostles. He then spent more than twenty years as a full-time author. He returned to the University of Cambridge and was Regius Professor of History from 1927 to 1943. He served as Master of Trinity College from 1940 to 1951. In retirement, he was Chancellor of Durham University.

Trevelyan was the third son of Sir George Otto Trevelyan, 2nd Baronet, and great-nephew of Thomas Babington Macaulay, whose staunch liberal Whig principles he espoused in accessible works of literate narrative avoiding a consciously dispassionate analysis, that became old-fashioned during his long and productive career.[4] The noted historian E. H. Carr considered Trevelyan to be one of the last historians of the Whig tradition.[5]

Many of his writings promoted the Whig Party, an important aspect of British politics from the 17th century to the mid-19th century, and its successor, the Liberal Party. Whigs and Liberals believed the common people had a more positive effect on history than did royalty and that democratic government would bring about steady social progress.[4]

Trevelyan's history is engaged and partisan. Of his Garibaldi trilogy, "reeking with bias", he remarked in his essay "Bias in History", "Without bias, I should never have written them at all. For I was moved to write them by a poetical sympathy with the passions of the Italian patriots of the period, which I retrospectively shared."[4]

Trevelyan was born into late Victorian Britain in Welcombe House, Stratford-on-Avon, the large house and estate owned by his maternal grandfather, Robert Needham Philips,[7] a wealthy Lancashire merchant and the Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) for Bury. Today Welcombe is a hotel and spa for tourists visiting Shakespeare's birthplace.[4] On his paternal side, he was the son of Sir George Trevelyan, 2nd Baronet, who had served as Secretary for Scotland, under Liberal Prime Ministers William Gladstone, and the Earl of Rosebery, and the grandson of Sir Charles Trevelyan, 1st Baronet, who had served as a civil servant and had faced considerable criticism for his and the British government's handling of the Great Famine of Ireland.

Trevelyan's parents used Welcombe as a winter resort after they inherited it in 1890. They looked upon Wallington Hall, the Trevelyan family estate in Northumberland, as their real home. George traced his father's steps to Harrow School and then Trinity College, Cambridge.[8] After attending Wixenford and Harrow, where he specialised in history, Trevelyan studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was a member of the secret society, the Cambridge Apostles and founder of the still existing Lake Hunt, a hare and hounds chase where both hounds and hares are human.[4] In 1898, he won a fellowship at Trinity with a dissertation that was published the following year as England in the Age of Wycliffe. One professor at the university, Lord Acton, enchanted the young Trevelyan with his great wisdom and his belief in moral judgement and individual liberty.[4]

Trevelyan made his own reputation by depicting Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi as a great hero who stood for British ideals of liberty. According to David Cannadine:

[Trevelyan's] great work was his Garibaldi trilogy (1907–11), which established his reputation as the outstanding literary historian of his generation. It depicted Garibaldi as a Carlylean hero—poet, patriot, and man of action—whose inspired leadership created the Italian nation. For Trevelyan, Garibaldi was the champion of freedom, progress, and tolerance, who vanquished the despotism, reaction, and obscurantism of the Austrian empire and the Neapolitan monarchy. The books were also notable for their vivid evocation of landscape (Trevelyan had himself followed the course of Garibaldi's marches), for their innovative use of documentary and oral sources, and for their spirited accounts of battles and military campaigns.[9]

Historian Lucy Voakes argues that his Garibaldi project was part of a larger movement among English intellectuals to consolidate, celebrate and sometimes to critique liberal culture and politics. She sees Trevelyan's conception of the hero, and his study of the Italian Risorgimento emerging from his promotion of a distinctly 'English' patriotism based upon Whig gradualism, parliamentary monarchy and a hierarchical anti-republicanism.[10]

Trevelyan lectured at Cambridge until 1903 at which point he left academic life to become a full-time writer. In 1927 he returned to the University to take up a position as Regius Professor of Modern History, where the single student whose doctorate he agreed to supervise was J. H. Plumb (1936). During his Professorship he was also familiar with

Guy Burgess – he gave a positive reference for Burgess when he applied for a post at the BBC in 1935, describing him as a "first rate man", but also stating that "He has passed through the communist measles that so many of our clever young men go through, and is well out of it".[11] In 1940 he was appointed as Master of Trinity College and served in the post until 1951 when he retired.

Trevelyan declined the presidency of the British Academy but served as chancellor of Durham University from 1950 to 1958. Trevelyan College at Durham University is named after him. He won the 1920 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for the biography Lord Grey of the Reform Bill, was elected a fellow of the British Academy in 1925, made a fellow of the Royal Society in 1950,[1] and was an honorary doctor of many universities including Cambridge.

During World War I he commanded a British Red Cross ambulance unit on the Italian front;[15] his defective eyesight meant he was unfit for military service.

Trevelyan was the first president of the Youth Hostels Association and the YHA headquarters are called Trevelyan House in his honour. He worked tirelessly through his career on behalf of the National Trust, in preserving not merely historic houses, but historic landscapes.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

George Macaulay Trevelyan OM CBE FRS FBA (16 February 1876[2] – 21 July 1962),[3] was a British historian and academic. He was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1898 to 1903.

He was part of the Cambridge

Apostles. He then spent more than twenty years as a full-time author. He returned to the University of Cambridge and was Regius Professor of History from 1927 to 1943. He served as Master of Trinity College from 1940 to 1951. In retirement, he was Chancellor of Durham University.

Trevelyan was the third son of Sir George Otto Trevelyan, 2nd Baronet, and great-nephew of Thomas Babington Macaulay, whose staunch liberal Whig principles he espoused in accessible works of literate narrative avoiding a consciously dispassionate analysis, that became old-fashioned during his long and productive career.[4] The noted historian E. H. Carr considered Trevelyan to be one of the last historians of the Whig tradition.[5]

Many of his writings promoted the Whig Party, an important aspect of British politics from the 17th century to the mid-19th century, and its successor, the Liberal Party. Whigs and Liberals believed the common people had a more positive effect on history than did royalty and that democratic government would bring about steady social progress.[4]

Trevelyan's history is engaged and partisan. Of his Garibaldi trilogy, "reeking with bias", he remarked in his essay "Bias in History", "Without bias, I should never have written them at all. For I was moved to write them by a poetical sympathy with the passions of the Italian patriots of the period, which I retrospectively shared."[4]

George Macaulay Trevelyan OM CBE FRS FBA (16 February 1876[2] – 21 July 1962),[3] was a British historian and academic. He was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1898 to 1903.

He was part of the Cambridge

Apostles. He then spent more than twenty years as a full-time author. He returned to the University of Cambridge and was Regius Professor of History from 1927 to 1943. He served as Master of Trinity College from 1940 to 1951. In retirement, he was Chancellor of Durham University.

Trevelyan was the third son of Sir George Otto Trevelyan, 2nd Baronet, and great-nephew of Thomas Babington Macaulay, whose staunch liberal Whig principles he espoused in accessible works of literate narrative avoiding a consciously dispassionate analysis, that became old-fashioned during his long and productive career.[4] The noted historian E. H. Carr considered Trevelyan to be one of the last historians of the Whig tradition.[5]

Many of his writings promoted the Whig Party, an important aspect of British politics from the 17th century to the mid-19th century, and its successor, the Liberal Party. Whigs and Liberals believed the common people had a more positive effect on history than did royalty and that democratic government would bring about steady social progress.[4]

Trevelyan's history is engaged and partisan. Of his Garibaldi trilogy, "reeking with bias", he remarked in his essay "Bias in History", "Without bias, I should never have written them at all. For I was moved to write them by a poetical sympathy with the passions of the Italian patriots of the period, which I retrospectively shared."[4]